Childhood Cancer Fact Library

Supported by SebastianStrong Foundation.

A comprehensive, well-documented and trusted source of information for anyone seeking data and statistics related to pediatric cancers. The Fact Library team updates its listing annually so that it can continue to be instrumental in building awareness of the realities associated with diagnosis, treatment, remission, and survivorship.

LATEST COMPLETE DATA YEAR: 2023 (Please note: Data is compiled each year and released at the end. 2024’s data will come next year. 2023 is the most current data available.)

All statistics below are for U.S. children from birth through age 19 unless stated otherwise. This summary relies on the most recent published data with respect to its contents, some of which dates back one or more years.

DIAGNOSIS

Note: This section contains facts for four groups: Children (ages 0-14), Children and Adolescents (ages 0-19), Adolescents (ages 15-19), Adolescents and Young Adults (Ages 15-39)

- Childhood and Adolescent cancer (ages 0-19) is not one disease – there are more than 12 major types of pediatric cancers and over 100 subtypes.(1)

- About 1 in 257 children and adolescents (aged 0-19) will be diagnosed with cancer before age 20.(1B)

- 47 children and adolescents per day or 17,293 (aged 0-19) were diagnosed with cancer in 2018.(45)

- The average age at diagnosis is 10 overall (ages 0 to 19), 6 years old for children (aged 0 to 14), and 17 years old for adolescents (aged 15 to 19)(9), while adults’ median age for cancer diagnosis is 66.(7a)

- The most common cancer types among children included leukemia, brain and other nervous system, and lymphoma, with cases increasing by 0.7% – 0.9% per year on average for all three types during 2001-2018.(7G)

- In the United States, the most common types of cancer diagnosed in 2016–2020among children and adolescents under age 20 were leukemia, malignant brain and other central nervous system (CNS) tumors, lymphomas, malignant soft tissue sarcomas, malignant germ cell tumors, and malignant bone tumors.(37)

- As of 2018, 4,317 children and teens under age 20 were diagnosed with CNS tumors, accounting for 25% of total cancer diagnoses in the age group 0-19.(45)

- Approximately 5.7% of newly diagnosed brain tumors, including adults, occur under age 20.(67)

- Childhood brain and other nervous system cancer is most frequently diagnosed among ages 5–9.(7H)

- Children with Down syndrome are 10 to 20 times more likely to develop leukemia than children without Down syndrome.(37)

- In 2024, an estimated 9620 children (aged birth to 14 years) will be diagnosed with cancer, and 1440 will die from the disease. 5290 adolescents (aged 15–19 years) will be diagnosed with cancer, and 550 will die.(1B)

- Among children aged 0-14, the incidence rate for all cancer sites combined was 17.8 cases per 100,000 persons. Incidence rates were stable (neither increased nor decreased) for children aged 0-14 between 2014 and 2018.(7G)

First time Cancer Diagnosis for Adolescents and Young Adults (AYA’s) Ages 15 to 39

- In 2023, it is estimated that there will be 85,980 new cases of cancer among AYAs in the United States. (40)

- Overall cancer incidence rates for AYAs increased an average of 0.9% per year between 2014 and 2018. The overall cancer incidence rate was 77.9 cases per 100,000 persons. (7G)

- The most common cancer among AYAs was female breast cancer, which was highest among Black AYAs. (7G)

SURVIVAL

- Cancer survival rates vary not only depending upon the type of cancer, but also upon individual factors attributable to each child. (6) Five year survival rates can range from almost 0% for cancers such as DIPG (2.2%(48)), a type of brain cancer, to over 90% for the most common type of childhood cancer known as Acute Lymphoma Leukemia (ALL).(1)

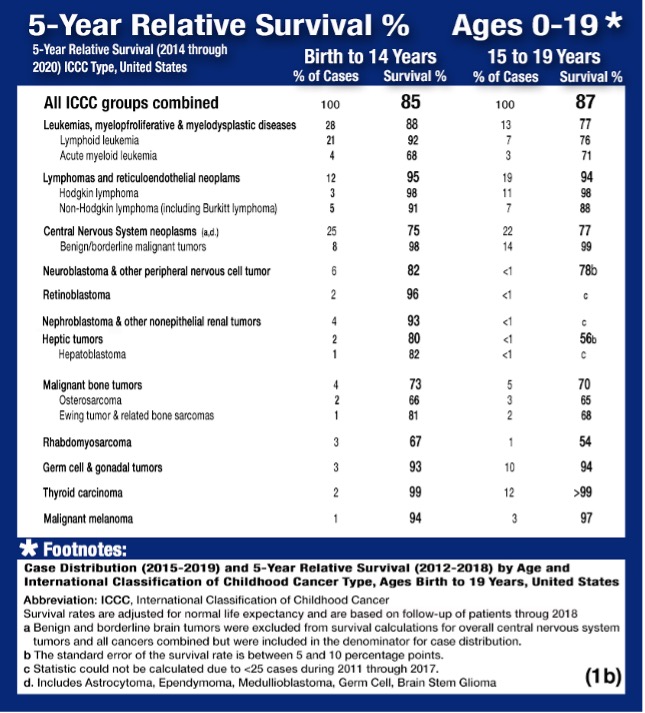

- The average 5-year survival rate for childhood cancer (Ages 0-19) as a whole is 86%.(1B)

- The most common severe or life-threatening chronic health problems related to childhood cancer or its treatment are endocrine disorders such as hypothyroidism or growth hormone deficiency (44%), subsequent neoplasms such as breast cancer or thyroid cancer (7%), and cardiovascular disease such as cardiomyopathy or congestive heart failure, coronary artery disease, and cerebrovascular disease (5.3%).(77)

- Individuals at highest risk for developing treatment-related health problems include patients with brain cancer treated with cranial irradiation (approximately 70% develop severe or life-threatening health problems) and allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients (approximately 60% develop severe or life-threatening health problems).(77)

- Individuals at the lowest risk for developing treatment-related health problems include those who survived solid tumors (such as Wilms tumor) treated with surgical resection alone or with minimal chemotherapy, for whom the prevalence of subsequent health problems is similar to people who did not have cancer during childhood or adolescence.(77)

- Diffuse Intrinsic Pontine Glioma (DIPG) represents approximately 80% of the malignant brainstem tumors occurring in children. (34) In the United States, about 300 children are diagnosed with DIPG each year. DIPG primarily affects children between the ages of 5 and 10 years but can occur in younger children and teens. DIPG is rare in adults.(7H)

- Despite numerous clinical trials, outcomes of children with DIPG continues to remain dismal, with a median survival of only 11 months, while only 10% of DIPG patients have a ≥ 2-year overall survival (OS) rate.(48)

- As of January 1, 2020 (the most recent date for which data exist), nearly 496,000 survivors of childhood and adolescent cancer (diagnosed at ages 0 to 19 years) were estimated to be alive in the United States. The number of survivors will continue to increase, given that the incidence of cancer in children and adolescents has been rising slightly in recent decades and that survival rates overall are improving.(27)

- Approximately 1 in 530 young adults aged 20 to 39, is a survivor of childhood cancer.(1)

LONG TERM HEALTH - LATE EFFECTS ASSOCIATED WITH TREATMENT & SURVIVORSHIP

- Cancer treatments may harm the body’s organs, tissues, or bones and cause health problems later in life. These health problems are called late effects as a result of surgery, chemotherapy, radiation therapy, and/or stem cell transplant. Late effects in childhood cancer survivors affect the body and mind. Late effects may affect organs, tissues, body function, growth and development. Other late affects are mood, feelings and actions thinking, learning, and memory as well as social and psychological adjustment. Late effects also have a risk of second cancers.(39)

- The chance of having late effects increases over time. New treatments for childhood cancer have decreased the number of deaths from the primary cancer. Because childhood cancer survivors are living longer, they are having more late effects after cancer treatment. Survivors may not live as long as people who did not have cancer. The most common causes of death in childhood cancer survivors are: The primary cancer comes back or a second (different) primary cancer forms or there is heart and lung damage.(39)

- Overall, children (ages 0-14) and AYA (ages 15-19) cancer survivors were 57% more likely to develop depression, 29% more likely to develop anxiety, and 56% more likely to develop psychotic disorders in the years following treatment compared to their siblings or healthy members of a control group.(82)

- Adult survivors of childhood cancer have a higher risk of developing cognitive impairment later in adulthood, according to study findings published in JAMA Network Open.(81)

- Childhood cancer survivors who received radiation or certain types of chemotherapy have an increased risk of late effects to the heart and blood vessels and related health problems.(39)

- NCI researchers observed that children who received radiotherapy had an increased risk of developing meningioma, cancer of the membranes that surround the brain and spinal cord (meninges).(72)

- Long-term follow-up analysis of a cohort of survivors of childhood cancer treated between 1970 and 1986 has shown that these survivors remain at risk of complications and premature death as they age, with more than half of them having experienced a severe or disabling complication or even death by the time they reach age 50 years.(63).

- Children and adolescents (ages 0 to 19) treated more recently, after 1986, may have lower risks of late effects due to modifications in treatment regimens to reduce exposure to radiotherapy, chemotherapy, and increased efforts to detect late effects, and improvements in medical care for late effects.(63)

- More than 95% of childhood cancer survivors will have a significant health related issue by the time they are 45 years of age; (41) these health related issues are late-effects of either the cancer or more commonly, the result of its treatment.

- 1/3 will suffer severe and chronic side effects;

- 1/3 will suffer moderate to severe health problems; and

- 1/3 will suffer slight to moderate side effects.(2)

- Cognitive impairment affects up to one-third of childhood cancer survivors.(38)

- Long-term survivors of childhood cancer may be at elevated risk for new neurocognitive impairment and decline as they age into adulthood.(86)

- A large follow-up study of pediatric cancer survivors found that almost 10% developed a second cancer (most commonly female breast, thyroid, and bone) over the 30-year period after the initial diagnosis.(38)

- Treatment for cancer may cause infertility in childhood cancer survivors. Infertility remains one of the most common and life-altering complications experienced by adults treated for cancer during childhood.(64)

- Having a bone marrow or stem cell transplant usually involves receiving high doses of chemotherapy and sometimes radiation to the whole body before the procedure. In most cases, this permanently stops ovaries from releasing eggs, resulting in lifelong infertility.(66)

- Female childhood cancer survivors who were treated with chemotherapy— even if they did not receive radiation treatments to their chest — are six times more likely than the general population to be diagnosed with breast cancer later in life. For those who did receive chest radiation, that chance increases exponentially and is on par with those who have the BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations.(28)

- Childhood cancer survivors are at a 15-fold increased risk of developing Congestive Heart Failure and are at 7-fold higher risk of premature death due to cardiac causes, when compared with the general population. There is a strong dose-dependent relation between anthracycline chemotherapy exposure and CHF risk, and the risk is higher among those exposed to chest radiation.(33)

- Children who were treated for bone cancer, brain tumors, and Hodgkin lymphoma, or who received radiation to their chest, abdomen, or pelvis, have the highest risk of serious late effects from their cancer treatment, including second cancers, joint replacement, hearing loss, and congestive heart failure.(37)

- Compared with the general population, survivors of childhood and adolescent cancers have an increased risk of 6 major psychiatric disorders, including: Autism spectrum disorder (hazard ratio [HR], 10.42), ADHD (HR, 6.59), PTSD (HR, 6.10), OCD (HR, 3.37), Major depressive disorder (HR, 1.88), Bipolar disorder (HR, 2.93).(62)

- Life expectancy for five-year childhood cancer survivors has steadily increased. Life expectancy for those treated in the 70’s is only 48.5 years and survivors treated in the 80’s have a life expectancy of 53.7 years, while those treated in the 90’s rose to 57.1 years.(41) Normal life expectancy for adults is 77.5 years.(7i)

- Nearly a quarter of childhood cancer survivors experience at least one debilitating neuromuscular condition 20 years post diagnosis.(47)

- Results published in Journal of Clinical Oncologyreveal that nearly 30% of childhood cancer survivors developed pre-diabetes compared with less than 20% of patients in a matched control group. Further analysis showed that between the ages of 40 and 49 years, more than 60% of the survivor group had either pre-diabetes or diabetes.(7)

- Overall, survivors treated with abdominopelvic radiotherapy treatment (ART) were three times more likely to develop a subsequent colorectal cancer (CRC) than those who did not receive ART.(10)

- The North American Children’s Oncology Group has developed long-term follow up guidelines (https://www.cmaj.ca/content/cmaj/suppl/2024/03/05/196.9.E282.DC1/231358-res-4-at.pdf ) to monitor adults who had cancer as children.(85)

FACTORS AFFECTING FOLLOW-UP CARE

Stakeholders GAO interviewed and studies GAO reviewed identified three factors that affect access to follow-up care for childhood cancer survivors—individuals of any age who were diagnosed with cancer from ages 0 through 19. These factors are care affordability, survivors’ and health care providers’ knowledge of appropriate care, and proximity to care. Childhood cancer survivors need access to follow-up care over time for serious health effects known as late effects—such as developmental problems, heart conditions, and subsequent cancers—which result from their original cancer and its treatment.

Affordability: Survivors of childhood cancer may have difficulty paying for follow-up care, which can affect their access to this care. For example, one study found that survivors were significantly more likely to have difficulty paying medical bills and delay medical care due to affordability concerns when compared to individuals with no history of cancer.

Knowledge: Survivors’ access to appropriate follow-up care for late effects of childhood cancer can depend on both survivors’ and providers’ knowledge about such care, which can affect access in various ways, according to stakeholders GAO interviewed and studies GAO reviewed:

-

- Some survivors may have been treated for cancer at an early age and may have limited awareness of the need for follow- up care.

- Some primary or specialty care providers may not be knowledgeable about guidelines for appropriate follow-up care, which can affect whether a survivor receives recommended treatment. Follow-up care may include psychosocial care (e.g., counseling), and palliative care (e.g., pain management).

Proximity: Survivors may have difficulty reaching appropriate care settings. Stakeholders GAO interviewed and studies GAO reviewed noted that childhood cancer survivors may have to travel long distances to receive follow-up care from multidisciplinary outpatient clinics—referred to as childhood cancer survivorship clinics. The lack of proximity may make it particularly difficult for survivors with limited financial resources to adhere to recommended follow-up care.

Pediatric Cancer 5-Year Ages 0 to19 for years 2014 through 2020: The table below is a representation of the estimated 5-year survival rates for various types of childhood cancers. It should be noted the survival rates listed below reflect general rates and are in no way a representation of an anticipated actual survival outcome for any individual child.

TREATMENT AND RESEARCH

- On average, in 2009 pediatric hospitalizations principally for cancer were 8 days longer and cost nearly 5 times as much as hospitalizations for other conditions (12.0 days versus 3.8 days; $40,400 versus $8,100 per stay). Costs per day were about 70 percent higher for pediatric cancer stays ($3,900 versus $2,300 per day).(5)

- In 2009, pediatric stays principally for cancer cost nearly one billion dollars, accounting for over 5 percent of pediatric non-newborn inpatient hospital costs.(5)

- One in four families lose more than 40% of their annual household income as a result of childhood cancer treatment-related work disruption, while one in three families face other work disruptions such as having to quit work or change jobs.(36)

- One in five children who receive a new diagnosis of childhood cancer are already living in poverty.(36)

- Parents of long-term childhood cancer survivors reported lower household income and higher risk-of-poverty. In a study group of 383 parents of long-term childhood cancer survivors, 30.4% reported lower household income and were at higher risk-of-poverty.(35)

- A 15-year trend for clinical trials on cellular therapy for children and adolescents (ages 0-19) with cancer in the US concluded that 169 (84%) of 202 trials posted 2007-2022 also included adult populations, only 3 trials enrolled children only. There was no industry funding for CNS tumors.(29)

- More than 90% of children and adolescents who are diagnosed with cancer each year in the United States are cared for at a children’s cancer center that is affiliated with the NCI-supported Children’s Oncology Group(COG). Children’s Oncology Group is the world’s largest organization that performs clinical research to improve the care and treatment of children and adolescents with cancer. Each year, approximately 4,000 children who are diagnosed with cancer enroll in a COG-sponsored clinical trial. COG trials are sometimes open to individuals aged 29 years or even older when the type of cancer being studied is one that occurs in children, adolescents, and young adults.(37)

FUNDING

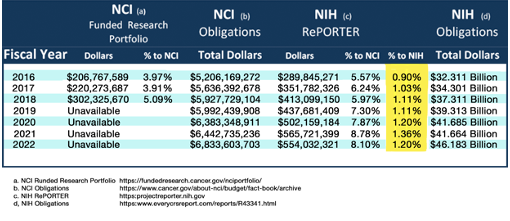

A report used in the past, often cited by advocates, is the NCI’s Funded Research Portfolio (NFRP). (7C) It indicates that from 2008 through 2018, the NCI spent an average of 4.08% of its obligations on childhood cancer research. According to NCI’s Office of Advocacy Relations (OAR), the NFRP does not reflect NCI’s total investment in any one particular area of research—including childhood cancers—because it does not account for basic science awards, which are not categorized by cancer type and which may have applications to multiple types of cancer. A preferred report by OAR, is the NIH RePORTER, which is a congressionally mandated system all NIH Institutes and Centers (ICs) use to report data by fiscal year (FY). This tool highlights annual support for various Research, Condition, and Disease Categories (RCDC) based on grants, contracts, and other funding mechanisms used across NIH. According to OAR, even the NIH RePORTER also does not account for the totality of NCI’s investment in a given area of research because basic science awards cannot be categorized by individual cancer type. Using Total NCI Obligations, without making allowances for NIH items included in the Pediatric Cancer Amount, would distort the percentage of Total Obligations.

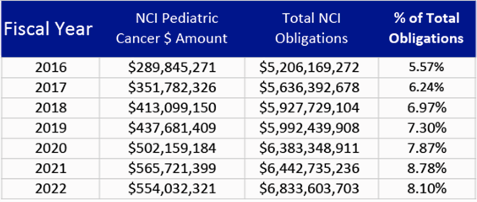

NIH RePORT Categorical Spending (RCDC) NCI – Pediatric Cancer Category

While both of the reports described above seem unable to capture a completely accurate measure of childhood cancer research expenditure as it relates to total research dollars, perhaps a better method to measure progress may be to compare NIH RePORTER pediatric dollars (c) to the Total NIH Dollars (d) for each fiscal year. This method would show changes from one year to the next. Note that the chart below shows growth in pediatric cancer expenditures from 2016 to 2022.

MORTALITY

- Cancer is the number one cause of death by disease among children and adolescents (ages 0-19) in the United States.(1B)

- On average, about 14% of children die within 5 years of diagnosis among those children, treated in the 70’s and 80’s, who survived to five years from diagnosis, 18% of them will die over the next 25 years. In recent decades, cancer treatments have been modified with the goal of reducing life-threatening late effects.(50)

- 1,040 children (aged 0 -14) and 550 adolescents (aged 15-19) are expected to die from cancer in 2024 (excluding benign and borderline malignant brain tumors). (1B) In 2023, it is estimated that there will be 9,050 deaths due to cancer among AYAs aged 15 to 39.(40)

- Between 1970 and 2020, patients with cancer aged 14 years and younger have experienced a 70% decline in overall cancer death rates. Adolescent patients aged 15 to 19 years experienced a 64% decrease over the same time span.(7F)

- Between 2015 and 2019, cancer death rates decreased an average of 1.5% per year among children ages 0 to 14, while death rates for AYAs (ages 15 to 39) decreased an average of 0.9% per year.(7G)

- Brain cancer represents 25% of total childhood cancer deaths while leukemia accounts for 28%.(1B)

- The median age at death for childhood brain and CNS cancers is age 9.(7H)

- The most common causes of death in childhood cancer survivors are: The primary cancer comes back. A second (different) primary cancer forms. Heart and lung damage.(39)

- Those that survive the five years have an eight times greater mortality rate due to the increased risk of liver and heart disease and increased risk for reoccurrence of the original cancer or of a secondary cancer.(8)

- There are 69.3 potential life years lost on average when a child dies of cancer(7B) compared to 12 potential life years lost for adults.(7i)

- Survivors of hereditary retinoblastoma, a rare cancer of the eye, have a high risk of developing subsequent cancers, particularly sarcomas of the soft tissue and bone.(73)

- “Despite improvements in 5-year survival, long-term survivors of childhood cancer are at four times the risk of death compared with the general, aging population.(83)

DRUG DEVELOPMENT

Highlighted drugs below were approved for children in the first instance.

- While more than 200 cancer drugs have been developed and approved for adults(58) the FDA, through December, 2023 has approved a total of 44 drugs for use in the treatment of childhood cancers. 38 of the drugs were originally approved only for adult use, then later for pediatrics. Today we have only six drugs that were approved in the first instance for use in cancer treatment for children: Teniposide (1992 for ALL) use now discontinued by NCI, clofarabine (2004 for ALL), dinutuximab (2015 for NB), tisagenlecleucel (2017 for ALL), calaspargase pegol-mk (2018 for ALL), selumetinib (2020 for NF1) and naxitamab (2020 for NB).(4) In addition, the FDA has approved 8 drugs that help to reduce the toxicity associated with certain cancer treatments.(75)

- The median lag time from first-in-human to first-in-child trials of oncology agents that were ultimately approved by FDA was 6.5 years.(61)

- Between the years of 2009 and 2019, nine of the 11 drugs used to treat acute lymphoblastic leukemia — which is the most common childhood cancer — were in and out of shortage.(32)

- Researchers found that the probability of FDA drug approval within 10 years was 10.4%, and the probability that development would stall within 10 years was 49.2%.(84)

- The FDA awarded Priority Review Vouchers (PRV) for four of the six drugs originally approved in the first instance for cancer treatment for children. PRV’s are transferable and are desired incentives for developers of drugs for rare pediatric diseases. Holders of a PRV get a faster FDA drug approval process for a future drug of their choice. The vouchers are transferable and may be sold or traded.(42)

- The US Congress created the priority review voucher program in 2007 based on a 2006 Health Affairs paper (Ridley et al. 2006). The voucher entitles the bearer to regulatory review in about six months rather than the standard ten months. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) awards a voucher following approval of a treatment for a neglected disease, rare pediatric disease (Cancer is included in rare pediatric disease) or medical countermeasure. Two drugs receive priority review for each voucher: the drug winning a voucher for a neglected or rare pediatric disease and the drug using a voucher for another indication. The voucher may be sold. For example, a small company might win a voucher for developing a drug for a neglected disease, and sell the voucher to a large company for use on a commercial disease. Vouchers can sell for 100’s of millions of dollars.(68)

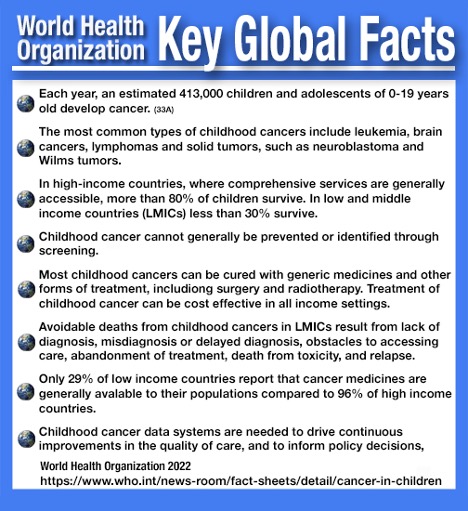

GLOBAL FACTS

- Global 5-year net childhood cancer survival is currently estimated at 37.4%.(46)

- In 2017, childhood cancer was the sixth leading cause of total cancer burden globally and the ninth leading cause of childhood disease burden globally.(70)

- Globally, in 2017, there were 11.5 million Disability Adjusted Life Years (DALYs) due to childhood cancer, 97.3% were attributable to Years of Life Lost (YLLs).(70)

- More than 90% of children at risk of developing childhood cancer each year live in low income and middle-income countries.(3)

- Approximately 1 in 15 children receiving cancer treatment in low- and middle-income countries die from treatment-related complications. Although treatment-related mortality has decreased in upper–middle-income countries over time, it remains unchanged in low- and middle-income countries.(31)

- Approximately 90% of children with cancer live in low-income and middle-income countries (LMICs), where 5-year survival is lower than 20%.(31)

- In 2019, cancer was the fourth leading cause of death and tenth leading cause of Disability-Adjusted Life Years (DALYs) in adolescents and young adults (ages 15 to 39) globally.(69)

- When the overall disease burden is studied within the age range encompassing adolescents and young adults (aged 15 years to 39 years), the global burden of cancer contributed more Disability-Adjusted Life Years (DALYs), a combination of Years of Life Lost (YLLs) and Years Lived with Disability (YLDs), to the global disease burden than some high-profile communicable diseases such as HIV/AIDS and sexually transmitted infections.(69)

- In 2019, 43% (172,000 of 397,000) of childhood cancer cases were undiagnosed globally.(78)

- Cancer kills more than 100,000 children (birth to 19) each year, and yet 80% of pediatric cancers are curable with currently available interventions. Notably, the majority of these deaths occur in low‐income and middle-income countries where children have poor access to health services.(33A)

- In Europe, since 1995, a total of 16 drugs have been approved for pediatric cancers. Seven of the 16 have been approved in the first instance specifically for pediatric cancers. Nine of the 16 were first approved for adults, then later for use in pediatric cancer. Eight of the total 16 drugs affected cancers responsible for less than 6% of all European childhood cancer deaths.(76)

- In 2018, The World Health Organization (WHO) launched the Global Initiative for Childhood Cancer with partners to provide leadership and technical assistance to support governments in building and sustaining high-quality childhood cancer programs. The goal is to achieve at least 60% survival rate globally by 2030, for all children with cancer. This represents an approximate doubling of the current cure rate and will save an additional one million lives over the next decade. The objectives are to increase capacity of countries to deliver best practices in childhood cancer care and also to prioritize childhood cancer and increase available funding at the national and global levels.(30)

- Some cancers are more prevalent in developing countries. For example, Burkitt’s lymphoma is more common in East and West Africa with over 4,000 cases in East Africa and over 10,000 in West Africa while only around 20 were recorded in the UK in 2015.(30)

- Because most of the world’s population is NOT covered by cancer surveillance systems or vital registration found in developed countries, and in addition, childhood cancer is rare and often presents with non-specific symptoms that mimic those of more prevalent infectious and nutritional conditions found in many low-income developing countries. Worldwide/UN-regional cancer incidence is therefore estimated using a Baseline Model (BM) method to quantify the cancer burden in children. It is estimated that there will be 13.7 million cases of childhood cancer between 2020-2050. Unless there are major improvements in diagnosis and treatments, of this, 45% will go undiagnosed and 11.1 million will die if no further investments in interventions are made. The vast majority, almost 85%, will be concentrated in developing countries.(33A)

- Current projections show that Africa will account for nearly 50% of the global childhood cancer burden by 2050.(71)

PSYCHOSOCIAL CARE

- Childhood cancer threatens every aspect of the family’s life and the possibility of a future, which is why optimal cancer treatment must include psychosocial care.(11)

- The provision of psychosocial care has been shown to yield better management of common disease-related symptoms and adverse effects of treatment such as pain and fatigue.(12)

- Depression and other psychosocial concerns can affect adherence to treatment regimens by impairing cognition, weakening motivation, and decreasing coping abilities.(13)

- For children and families, treating the pain, symptoms, and stress of cancer enhances quality of life and is as important as treating the disease.(14)

- Childhood cancer survivors reported higher rates of pain, fatigue, and sleep difficulties compared with siblings and peers, all of which are associated with poorer quality of life.(15)

- Changes in routines disrupt day-to-day functioning of siblings.16 Siblings of children with cancer are at risk for emotional and behavioral difficulties, such as anxiety, depression, and post traumatic stress disorder.(17)

- Symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder are well documented for parents whose children have completed cancer treatment.(18)

- Chronic grief has been associated with many psychological (e.g., depression and anxiety) and somatic symptoms (e.g., loss of appetite, sleep disturbances, fatigue), including increased mortality risk.(19)

- Cancer survivors in the United States reported medication use for anxiety and depression at rates nearly two times those reported by the general public, likely a reflection of greater emotional and physical burdens from cancer or its treatment.(21)

- Financial hardship during childhood cancer has been found to affect a significant proportion of the population and to negatively impact family wellbeing.(22)

- Adolescents with cancer experienced significantly more Health Related Hindrance (HRH) of personal goals than healthy peers, and their HRH was significantly associated with poorer health-related quality of life, negative affect, and depressive symptoms.(23)

- Peer relationships of siblings of children with cancer are similar to classmates, though they experience small reductions in activity participation and school performance.(24)

- Chronic health conditions resulting from childhood cancer therapies contribute to emotional distress in adult survivors.(25)

- Parents have been found to report significant worsening of all their own health behaviors, including poorer diet and nutrition, decreased physical activity, and less time spent engaged in enjoyable activities 6 to 18 months following their child’s diagnosis.(26)

PREVENTION

- Any substance that causes cancer is known as a carcinogen. But simply because a substance has been designated as a carcinogen does not mean that the substance will necessarily cause cancer. Many factors influence whether a person exposed to a carcinogen will develop cancer, including the amount and duration of the exposure and the individual’s genetic background.(79)

- Cancers caused by involuntary exposures to environmental carcinogens are most likely to occur in subgroups of the population, such as workers in certain industries who may be exposed to carcinogens on the job.(79)

- Two organizations—the National Toxicology Program (NTP), an interagency program of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), and the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC), the cancer agency of the World Health Organization—have developed lists of substances that, based on the available scientific evidence, are known or are reasonably anticipated to be human carcinogens.(79)

- The National Toxicology Program (NTP) cumulative report now includes 256 listings of substances — chemical, physical, and biological agents; mixtures; and exposure circumstances — that are known or reasonably anticipated to cause cancer in humans. The latest report, the 15th Report on Carcinogens was released on December 21, 2021. (https://ntp.niehs.nih.gov/whatwestudy/assessments/cancer/roc)(80)

- Childhood cancer is fundamentally different to adult cancer in its biology, clinical classification, and treatment. Most childhood cancers are not caused by modifiable risk factors, public health campaigns would not have a large effect on decreasing their incidence.(56)

- Over the past 50 years, the use of artificial chemicals in products has increased exponentially. Most of these chemicals were not tested for safety before widespread use, and the impacts of exposures are just now being realized. Children are especially vulnerable to the health impacts of chemical exposures, and these exposures are now known to be an important component of rising rates of diseases such as asthma, some cancers, and neurodevelopmental disorders in children.(74)

- Children are at an elevated risk for chronic disease because of increased exposure to environmental toxins. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) (2017) identifies children as uniquely vulnerable to environmental risks because of rapidly developing brains, lungs, immune and other bodily systems with less developed natural defenses than adults, including more permeable blood-brain barriers, and metabolic and detoxification pathways that are not yet fully developed.(74)

- Phthalates are a class of chemicals found in a variety of products. They are mixed with polyvinyl chloride and other plastics as a plasticizer that helps to make them soft and flexible. They are also added to cosmetics and other personal care products (often as a fragrance stabilizer), in medical equipment and coatings on medications, food production equipment and packaging, flooring, wall coverings, and other home products. (74) In a study of 1.3 million children aged under 19 years of age, childhood phthalate exposure was associated with incidence of osteosarcoma and lymphoma.(60)

- Pesticides are a group of chemicals intended to kill unwanted insects, plants, molds, and rodents, making them inherently toxic chemicals. Pesticides are not species-specific in their neurotoxic properties—a wanted effect on the nervous system of an insect can also be an unwanted effect on the nervous system of a child. (74) Exposures to pesticides, tobacco smoke, solvents, and traffic emissions have consistently demonstrated positive associations with risk of developing childhood leukemia.(53)

- Researchers found a higher level of common household pesticides in the urine of children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. The findings should not be seen as cause-and-effect, but suggests an association between pesticide exposure and development of childhood ALL.(59)

- The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) reports that 75 percent of U.S. households used at least one pesticide product indoors during the past year. The EPA also states, “Exposure to pesticides may result in irritation to eye, nose and throat, damage to central nervous system, kidney and increased risk of cancer.”(52)

- Exposure to toxic substances, such as industrial chemicals and radiation, can increase the risk of leukemia. People may encounter radiation during imaging tests such as MRI scans, X-rays, and CT scans. (57)

- Since children are more radiosensitive than adults and although CT scans are very useful clinically, potential cancer risks exist from associated ionizing radiation.(54)

- Exposure of parents to ionizing radiation is also a possible concern in terms of the development of cancer in their future offspring. Children whose mothers had x-rays during pregnancy (that is children who were exposed before birth) and children exposed after birth to diagnostic medical radiation from computed tomography (CT) scans have been found to have a slight increase in risk of leukemia and brain tumors and possible other cancers.(37)

- Risk of childhood leukemia was associated with higher crop area near mother’s homes during pregnancy; CNS tumors were associated with higher cattle density.(51)

- Intake of vitamins and folate supplementation during the preconception period or pregnancy has been demonstrated to have a protective effect.(55)

ENDNOTES

1 American Cancer Society, Childhood and Adolescent Cancer Statistics, 2014

https://www.cancer.org/content/dam/cancer-org/research/cancer-facts-and-statistics/annual-cancer-facts-and-figures/2014/special-section-cancer-in-children-and-adolescents-cancer-facts-and-figures-2014.pdf

1B Rebecca L. Siegel MPH, Angela N. Giaquinto MSPH, Ahmedin Jemal DVM, PhD, A Cancer Journal for Clinicians,

Cancer Statistics 2024, https://acsjournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.3322/caac.21820

2 St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital, (JAMA. 2013:309 [22]: 2371-2381)

http://jama.jamanetwork.com/article.aspx?articleid=1696100

3 Lancet Oncology, Sep 2019 Volume 20 Number 9 p1211– p1225, “The global burden of childhood and adolescent cancer in 2017”

https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lanonc/article/PIIS1470-2045(19)30339-0/fulltext

4 National Cancer Institute, http://www.cancer.gov/research/areas/childhood, February 8, 2024

https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/treatment/drugs/childhood-cancer-fda-approved-drugs

5 Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, US Dept. of Health & Human Services, “Pediatric Cancer Hospitalizations 2009, May 2012, Rebecca Anhang Price, Ph.D., Elizabeth Stranges, M.S., and Anne Elixhauser, Ph.D.

https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb132.jsp

6 American Society of Clinical Oncology

http://jco.ascopubs.org/content/28/15/2625.short

7 HemOnc today, “Survivors of childhood cancer have increased risk for prediabetes,” January 25, 2024, Josh Friedman,

https://www.healio.com/news/hematology-oncology/20240125/survivors-of-childhood-cancer-have- increased-risk-for-prediabetes

7A National Cancer Institute,“ Age and Cancer Risk” 3/05/2021. Source: SEER 21 2013–2017, all races, both sexes.

https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/causes-prevention/risk/age

7B National Cancer Institute, SEER Cancer Statistics Review 1973-1997 (NCI 2000)

http://jnci.oxfordjournals.org/content/93/5/341.full

7C National Cancer Institute, NIH/NCI

https://fundedresearch.cancer.gov/nciportfolio/stats.jsp

7D National Cancer Institute, NIH/NCI

https://fundedresearch.cancer.gov/nciportfolio/about.jsp

7E National Cancer Institute, Cancer Types, Diffuse Intrinsic Pontine Glioma (DIPG)

https://www.cancer.gov/types/brain/patient/diffuse-intrinsic-pontine-glioma

7F Healio HemOnc Today, “Cancer death rate drops by 33%, AACR report shows,” September 13, 2023, Matthew Shinkle, https://www.healio.com/news/hematology-oncology/20230913/aacr-report-details-33-drop-in-us-cancer-death-rate

7G Annual Report to the Nation 2022: Overall Cancer Statistics

https://seer.cancer.gov/report_to_nation/statistics.html#new

7H National Cancer Institute, SEER Cancer Stat Facts: Childhood Brain and Other Nervous System Cancer (Ages 0–19),

“Percent of New cases by Age Group,” https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/childbrain.html

7i National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS): National Vital Statistics System (NVSS) “Provisional Life Expectancy Estimates 2022, Report #31, Nov. 2023 https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/vsrr/vsrr031.pdf

8 Journal of the National Cancer Institute, “Cause-Specific Late Mortality Among 5 Year Survivors”

http://jnci.oxfordjournals.org/content/100/19/1368.full

9 Howlader N, Noone AM, Krapcho M, Miller D, Brest A, Yu M, Ruhl J, Tatalovich Z, Mariotto A, Lewis DR, Chen HS, Feuer EJ, Cronin KA (eds). SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975-2018, National Cancer Institute. Bethesda, MD,

Based on November 2020 SEER data submission, posted to the SEER web site, April 2021.

10 Journal of Clinical Oncology – ORIGINAL REPORTS, November 16, 2023, Volume 42, Number 3,

https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.23.00452

11 Institute of Medicine, 2008 – Cancer Care for the Whole Patient

12 Jacobsen et al., 2012 (Journal of Clinical Oncology, 30 (11), p.1151-1153)

13 Institute of Medicine, 2008

14 Institute of Medicine 2015 – Comprehensive Care for Children with Cancer and Their Families

15 Children’s Oncology Group Long Term Follow-Up Guidelines, 2013

16 Alderfer et al., 2010 (Psycho-oncology, 19 (8), p. 789-805)

17 Alderfer et al., 2003 (Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 28 (4), p. 281-286)

18 Kazak et al., 2004 (Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 29 (3), p. 211-219)

19 Alam et al., 2012 (Death Studies, 36 (1), p. 1-22)

20 Psychosocial care addresses the effects that cancer treatment has on the mental health and emotional wellbeing of patients, their family members, and their professional caregivers. A single profession alone does not provide psychosocial care: Instead, every patient-healthcare provider interaction provides an opportunity to assess the stressors and concerns of children and their family members.

21 Hawkins et al., 2017 (Journal of Clinical Oncology, 5 (1), 78-87)

22 Bona et al., 2014 (Journal of Pain Symptom Management, 47 (3), 594-600)

23 Schwartz & Brumley, 2017 (Journal of Adolescent & Young Adult Oncology, 6 (1), 142-149)

24 Alderfer et al., 2015 (Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 40 (3) 309–319)

25 Vuotto et al., 2017 (Cancer, 123 (3), 521-528)

26 Wiener et al., 2016 (Journal of Pediatric Oncology Nursing, 33(5), 378–386)

27 National Cancer Institute, “Childhood Cancer Survivor Study: An Overview,” September 7, 2023

https://www.cancer.gov/types/childhood-cancers/ccss

28 UChicago Medicine, Tara Henderson, MD, MPH, “Understanding risks for childhood cancer survivors,” 9/01/2023,

https://www.uchicagomedicine.org/forefront/cancer-articles/understanding-risks-for-childhood-cancer- survivors

29 Cho S, Miller A, Mosha M, et al. (October 28, 2023) Clinical Trials on Cellular Therapy for Children and Adolescents With Cancer: A 15-Year Trend in the United States. Cureus 15(10): e47885. DOI: 10.7759/cureus.47885

30 World Health Organization 2021 Dec. 13, “Childhood Cancer: Key Facts,”

https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/cancer-in-children

31 The Lancet Oncology, VOLUME 24, ISSUE 9, P967-977, SEPTEMBER 2023, Treatment-related mortality in children with cancer in low-income and middle-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis

https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lanonc/article/PIIS1470-2045(23)00318-2/abstract

32 FDA Report Drug Shortages

https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-shortages/report-drug-shortages-root-causes-and-potential-solutions

33 Lancet Oncology. 2015 Mar; 16(3): e123–e136. doi: 10.1016/S1470- 2045(14)70409-7

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4485458/

33A Lancet Oncology. “Sustainable care for children with cancer.” 04/2020 Volume 21 Number 4p467-602, e180-e225:

https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lanonc/article/PIIS1470-2045(20)30022-X/abstract

34 Effect of Time from Diagnosis to Start of Radiotherapy on Children with Diffuse Intrinsic Pontine Glioma

2014 Jan 30. Doi: 10.1002/pbc.24971 PMCID: PMC4378861NIHMSID: NIHMS667729 PMID: 24482196

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4378861/

35 Household income and risk-of-poverty of parents of long-term childhood cancer survivors, Pediatric Blood Cancer, 2017 Aug; 64(8). Doi: 10.1002/pbc.26456. Epub 2017 Mar 6. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28266129/

36 The National Children’s Cancer Society, The Economic Impact of Childhood Cancer, November 30, 2018

Retrieved from https://policycommons.net/artifacts/1647909/the-economic-impact-of-childhood-cancer/

on 16Dec 2021. CID:20.500.12592/qp3g3v.

37 The National Cancer Institute “Cancer in Children and Adolescents” 9/27/2023

https://www.cancer.gov/types/childhood-cancers/child-adolescent-cancers-fact-sheet

38 American Cancer Society, Treatment and Survivorship Statistics, 2019 https://acsjournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.3322/caac.21565

39 National Cancer Institute, NIH/NCI Late Effects of Treatment for Childhood Cancer (PDQ®)–Patient Version

https://www.cancer.gov/types/childhood-cancers/late-effects-pdq

40 National Cancer Institute, Cancer Stat Facts: Cancer Among Adolescents and Young Adults (AYAs) (Ages 15–39) https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/aya.html

41 The ASCO Post “Many Survivors of Childhood Cancer Experience Lifelong Chronic Health Problems and Shorter Lifespans Than Their Healthier Peers,” October 16, 2023, Jo Cavallo. https://ascopost.com/news/october-2023/many-survivors-of- childhood-cancer-experience-lifelong-chronic-health-problems-and-shorter-lifespans-than-their-healthier-peers/

42 Food and Drug Administration, FDA, 12,27,2020, Rare Pediatric Disease (RPD) Designation and Voucher Programs

https://www.fda.gov/industry/developing-products-rare-diseases-conditions/rare-pediatric-disease-rpd- designation-and-voucher-programs

43 United States Government Accounting Offices, GAO-20-636R, Jul 31, 2020. “Survivors of Childhood Cancer: Factors Affecting Access to Follow-up Care” https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-20-636r

44 DELETED

45 NIH/National Cancer Institute, Age-Adjusted and Age-Specific SEER Cancer Incidence Rates, 2014-2018, Table 2.1

https://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2018/results_single/sect_02_table.01_2pgs.pdf

46 Lancet Oncology, Volume 20, Issue 7, July 2019, Pages 972-983, “Global childhood cancer survival estimates and priority- setting: a simulation-based analysis,” https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1470204519302736

47 Cancer Epidemiology Biomarkers, 1 August 2021, DOI:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-21-0154

https://aacrjournals.org/cebp/article-abstract/30/8/1536/670996/Longitudinal-Evaluation-of-Neuromuscular

48 Hofmann et al. (J Clin Oncol, 2018 vol. 36(19) pp. 1963-1972)

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29746225/

49 DELETED

50 New England Journal of Medicine, Armstrong GT, Chen Y, Yasui Y, et al. Reduction in late mortality among 5-year survivors of childhood cancer. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:833-842.

https://www.nejm.org/doi/10.1056/NEJMoa1510795

51 Residential proximity to agriculture and risk of childhood leukemia and central nervous system tumors in the Danish national birth cohort. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32711331/

52 US Environmental Protection Agency. Pesticides and Child Safety. Washington, DC: US Environmental Protection Agency; “Pesticides’ Impact on Indoor Air Quality,”

https://www.epa.gov/indoor-air-quality-iaq/pesticides-impact-indoor-air-quality

53 Science Digest. “Current Problems in Pediatric and Adolescent Health Care,” Volume 46, Issue 10, October 2016, Pages 317-352, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1538544216300694

54 Lancet. 2012 Aug 4;380(9840):499-505. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60815-0.Epub 2012 Jun 7. “Radiation exposure from CT scans in childhood and subsequent risk of leukaemia and brain tumours: a retrospective cohort study,”PubMed https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22681860/

55 American Academy of Pediatrics, “Childhood Leukemia: A Preventable Disease,” Volume 138, Issue Supplement_1, November 2016, https://publications.aap.org/pediatrics/article- abstract/138/Supplement_1/S45/34075/Childhood-Leukemia-A-Preventable-Disease

56 The Lancet. 4/1/2020 Volume 21Number 4, p.489, “Sustainable care for indigenous children with cancer.”

https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lanonc/article/PIIS1470-2045(20)30137-6/fulltext

57 Medical News Today, “Is leukemia hereditary?” by Jamie Eske, May 30, 2019

https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/325332

58 JAMA Network 3/15/2022 Volume 5 Number 3, doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.2265. “Cancer Drug Approvals That Displaced Existing Standard-of-Care Therapies, 2016-2021,” David J. Benjamin, MD; Alexander Xu, BA; Mark P. Lythgoe, MBBS; et al

https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamanetworkopen/fullarticle/2790102

59 Georgetown University Medical Center “Common Household Pesticides Linked To Childhood Cancer Cases In Washington Area”: August 4, 2009, https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2009/07/090728102306.htm

60 CTVNews, HEALTH News, 3/18/2022, “Exposure to ‘everyday chemical’ associated with higher incidence of childhood cancer: study, Journal of the National Cancer Institute 2/18/2022: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35179607/

61 European Journal of Cancer, Volume 112 pg. 49-56, May 1, 2019, “Timing of first-in-child trials of FDA-approved oncology drugs.” Dylan V, Neel, David S. Shulman, Steven G. Dubois. Published March 28, 2019, DOI:

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2019.02.011

62 Hsu T-W, Liang C-S, Tsai S-J, et al. Risk of major psychiatric disorders among children and adolescents surviving malignancies: A nationwide longitudinal study. https://ascopubs.org/doi/abs/10.1200/JCO.22.01189 J Clin Oncol. Published online January 17, 2023. doi:10.1200/JCO.22.01189

63 National Cancer Institute, “Cancer in Children and Adolescents,” November 4, 2021,

https://www.cancer.gov/types/childhood-cancers/child-adolescent-cancers-fact-sheet#what-should- survivors-of-childhood-and-adolescent-cancer-consider-after-they-complete-treatment

64 Hudson MM. Reproductive outcomes for survivors of childhood cancer. Obstet Gynecol. 2010 Nov;116(5):1171-83. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181f87c4b. PMID: 20966703; PMCID: PMC4729296.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4729296/

65 DELETED

66 American Cancer Society, How Cancer and Cancer Treatment Can Affect Fertility in Females, “Bone marrow or stem cell transplant,” Page 7 https://www.cancer.org/treatment/treatments-and-side-effects/physical-side- effects/fertility-and-sexual-side-effects/fertility-and-women-with-cancer/how-cancer-treatments-affect- fertility.html

67 National Brain Tumor Society, Brain Tumor Facts, Brain Tumors in All Pediatric Populations (0-19)

https://braintumor.org/brain-tumors/about-brain-tumors/brain-tumor-facts/

68 Duke University, Fuqua School of Business, Dr. David Ridley, Dr. and Mrs. Frank A. Riddick,

Priority Review Vouchers, Home Website, Overview: https://sites.fuqua.duke.edu/priorityreviewvoucher/

69 The Lancet. Oncology, January 2022, *, ISSUE 1, P27-52, The global burden of adolescent and young adult cancer in 2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019

https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lanonc/article/PIIS1470-2045(21)00581-7/fulltext

70 The Lancet. Oncology, September 2019, Volume 20, Issue 9, Pages 1211-1225,

The global burden of childhood and adolescent cancer in 2017: an analysis of the Global Burden of Disease Study

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1470204519304243

71 World Health Organization, WHO Regional Director for Africa, Dr. Matshidiso Moeti, 04 February 2023

Message, 771 https://www.afro.who.int/regional-director/speeches-messages/world-cancer-day-2023

72 National Cancer Institute, Division of Cancer Epidemiology & Genetics: Increased Meningioma Risk

Following Treatments for Childhood Cancer

https://dceg.cancer.gov/news-events/news/2022/meningioma-risk-childhood-cancer

73 National Cancer Institute, Division of Cancer Epidemiology & Genetics: February 11, 2021,

“Subsequent Cancer Risk in Retinoblastoma Survivors”

https://dceg.cancer.gov/news-events/news/2021/retinoblastoma-subsequent-cancer-risk

74 Journal of Pediatric Health Care, Pediatric Chemical Exposure: Opportunities for Prevention

Volume 36, Issue 1, January–February 2022, Pages 27-33

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0891524521002194

75 NIH National Library of Medicine, “Supportive care medications coinciding with chemotherapy among

children with hematologic malignancy,” HHS Author manuscript; available in PMC 2020 Dec 9 PMCID: PMC7725403 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7725403/

76 Lancet Child Adolescent Health. 2023 Mar;7(3):214-222. doi: 10.1016/S2352-4642(22)00344-3. Epub.

2023 Jan19. “Impact of the EU Paediatric Medicine Regulation on new anti-cancer medicines for the treatment of children and adolescents.” https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36682367/

77 JAMA Network. Bhatia S, Tonorezos ES, Landier W. Clinical Care for People Who Survive Childhood Cancer: A Review. JAMA. 2023;330(12):1175–1186. doi:10.1001/jama.2023.16875

78 The Lancet Oncology, Feb. 26 2019, Volume 20, Issue 4, Pages 483-493, “Estimating the total incidence of global childhood cancer:” a simulation-based analysis” DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30909-4

79 National Cancer Institute, NIH/NCI, “Environmental Carcinogens and Cancer Risk,” April 6, 2023,

https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/causes-prevention/risk/substances/carcinogens

80 National Toxicology Program, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 15th Report on Carcinogens

https://ntp.niehs.nih.gov/whatwestudy/assessments/cancer/roc/data

81 Neurology Advisor, “Adult Childhood Cancer Survivors at Risk for Cognitive Impairment With Age,”

July 11, 2023, Based on JAMA report doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.16077 https://www.neurologyadvisor.com/topics/neurocognitive-disorders/adult-childhood-cancer-survivors-risk- cognitive-impairment-age/

82 STAT News, Health, June 28, 2023, “When young people survive cancer, their mental-health struggles are often just beginning” https://www.statnews.com/2023/06/28/cancer-young-people-mental-health/

83 Cancer Therapy Advisor, “Pediatric Cancer Survivors Have 4-Fold Higher Risk of Death 40 Years After Diagnosis,” Julie Ehlers, April 13, 2023. https://www.cancertherapyadvisor.com/home/news/pediatric- cancer-survivors-4-fold-higher-risk-death-40-years-after-diagnosis/

84 Cancer Therapy Advisor, “Few Cancer Drugs Are Approved Within 10 Years of Entering Trials,” Andrea S. Blevins Primeau, PhD, MBA, May 24, 2023. https://www.cancertherapyadvisor.com//home/cancer- topics/general- oncology/few-cancer-drugs-approved-within-10-years-entering-trials/

85 Canadian Medical Association Journal. 11/14/2024, Researchers at The Hospital for Sick Children (Sick Kids) and Women’s College Hospital, “Longitudinal adherence to surveillance for late effects of cancer treatment: a population-based study of adult survivors of childhood cancer,”

https://www.cmaj.ca/lookup/doi/10.1503/cmaj.231358

86 JAMA Open Network, May 31, 2023. Ms Stratton and Dr. Leisenring, “Late-onset Cognitive Impairment and Modifiable Risk Factors in Adult Childhood Cancer Survivors,”

doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.16077 https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamanetworkopen/fullarticle/2805444

THIS DOCUMENT IS NOT INTENDED TO OFFER SPECIFIC STATISTICS REGARDING AN INDIVIDUAL PATIENT OR THE PATIENT’S SPECIFIC FORM OF CANCER AND IS NOT A SUBSTITUTE FOR INFORMATION THAT MAY BE SOUGHT FROM A PHYSICIAN. IT IS MERELY INTENDED, BASED ON INFORMATION PRESENTLY AVAILABLE TO THE AUTHORS, TO BE A GOOD FAITH GENERAL PRESENTATION OF CHILDHOOD CANCER STATISTICS THAT MAY BE HELPFUL TO OTHERS SEEKING SUCH GENERAL INFORMATION.

March 31, 2024