INTRODUCTION

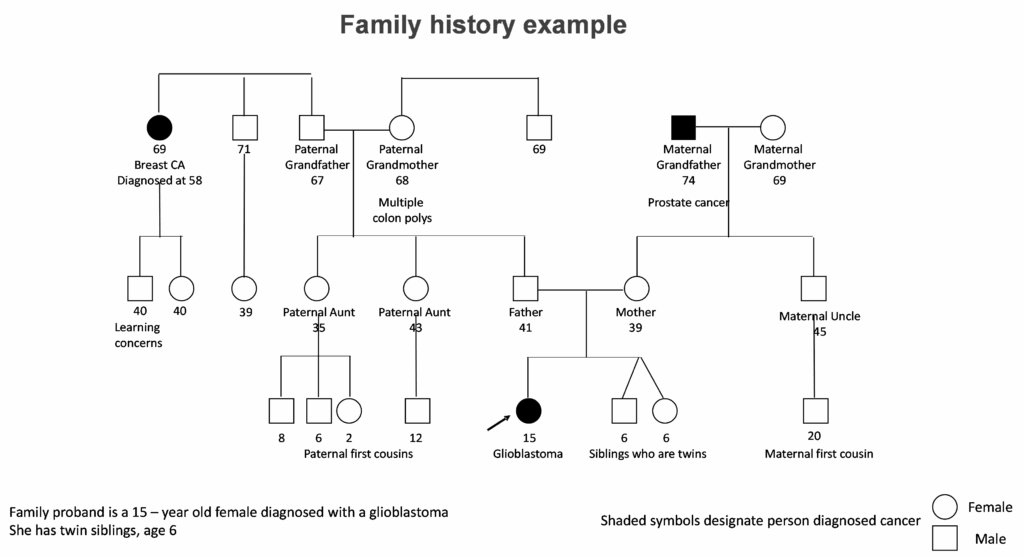

Did you ever ask if your child’s cancer could be “genetic”? Have you considered if your family cancer history could be related to your child’s diagnosis of cancer, even though the cancer diagnoses were not the same type? Did you question how genetic testing may be helpful for your child? Did you discuss if your other children or other family members could have a higher chance to develop cancer? If your child had genetic testing, have you considered if updated information may be informative for your child’s care or the care of other family members?

If you asked yourself these and similar questions, you were considering the possibility your child has an inherited cancer syndrome. This section describes information about genetics – information about our inherited genetic make-up as well as tumor genetics. The primary focus is on inherited genetics with information pertaining to inherited cancer predisposition syndromes and how this information is used to guide a child’s care, both during cancer treatments and survivorship, and potentially the care of other family members.

BASIC INFORMATION – GENES AND CANCER

Every person has over 20,000 genes in every cell of the body. Our genes, or DNA, not only determine what we look like, such as our eye color or texture of our hair. Our genes determine how cells function within the body. For example, our genes determine that colon cells have a different structure and function than our brain cells. Our genes also control how cells grow and divide.

A cancer or tumor develops when cells have lost their ability to stop making new cells.

For most children, cancer develops sporadically. That is, a single cell spontaneously develops a gene mutation. Over time, as this cell makes more cells, additional gene mutations occur, but only in those cells. If these cells accumulate a sufficient number or type of gene mutations, the cells lose their ability to stop growing, forming a cancer.

In contrast, children with an inherited cancer predisposition syndrome have a gene mutation that was present from the time the child was conceived. That gene mutation is present in all the cells. Certain gene mutations lead to a higher chance for certain cancers to develop, and sometimes, these tumors develop in childhood. This factsheet reviews general information about gene mutations that are associated with an increased chance for cancer, that is gene mutations that cause cancer predisposition syndromes.

INHERITED CANCER PREDISPOSITION SYNDROMES

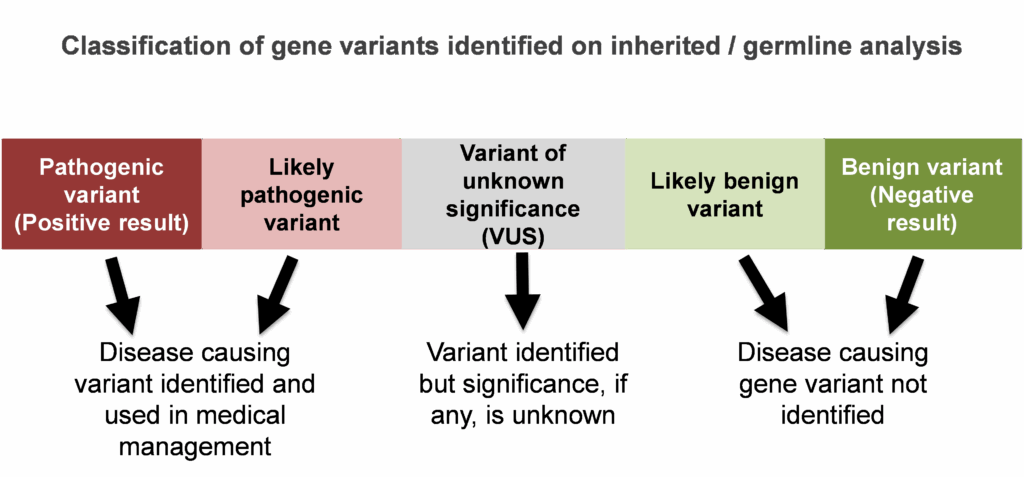

Every person has gene mutations. Mutations, also known as pathogenic variants, disrupt a gene’s normal, everyday function. Mutations do not allow the gene to function properly. Some mutations are not important for a person’s overall health and wellbeing. Consider for example a person with a gene mutation that only causes premature grey hair. While that person may not like grey hair at a younger age, it is not an important health consideration. Other mutations, do matter, like mutations which cause an increased risk for certain types of cancer.

An inherited cancer predisposition syndrome result from a gene mutation found in a person’s inherited genetic make-up, or DNA. Some people may use the term, hereditary cancer. Individuals with an inherited cancer predisposition syndrome have an increased risk for certain types of cancer. Having a gene mutation associated with higher cancer risk does not mean a person will ever develop a cancer. However, it does mean they have a higher chance for certain cancers compared to people of the same age and gender, and as such, additional cancer screening and medical care would be recommended for that individual.

Having an inherited cancer predisposition syndrome typically does not mean your child has a higher chance of experiencing a recurrence of their cancer. The chance that a child’s tumor will recur is often based on other factors, such as the size and grade of the tumor, and if the child had lymph node involvement with their cancer.

Why would a family want to know if they had an inherited cancer predisposition syndrome? Knowing if a child has an inherited syndrome may help to guide treatment as well as ongoing medical surveillance. Likewise, in some situations, there is scientific evidence that demonstrate certain gene mutations make treatments less effective.